01 City on the sea

The city on the wide South Wales bay, once compared to the Bay of Naples, could be in for a big tourism boost, as we look for short breaks closer to home.

In Wales the year 2018 is designated Year of the Sea. The Welsh government wants 2018 to be an opportunity for Wales to make its mark as the UK’s top 21st century coastal destination. And no place can claim to be more linked to the sea through its history and geographical situation than Swansea.

In Dec 2017 Swansea University successfully raised £100,210 in the #bikes4swansea campaign, and went on to win the Santander Cycles University Challenge to launch a cycle sharing scheme in the city. In May 2018 @SantanderCycles launched a new cycle scheme for Swansea.

http://www.crowdfunder.co.uk/bikes4swansea/?

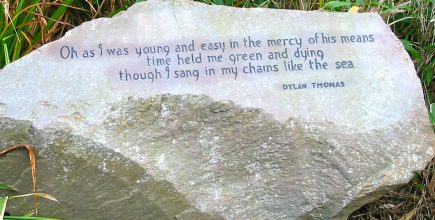

The city on the wide South Wales bay, Dylan Thomas’s “ugly lovely town”, is well placed to benefit as a staycation tourist destination as the British eschew foreign travel because of the poor exchange rate. Swansea is a city with a Premiership football club, a leading rugby club, the Ospreys, huge beaches, great museums, Britain’s pioneer beauty spot (Gower), a ghostly pub, and the house where Dylan grew up. The artist Turner depicted its charms in his “View across Swansea Bay 1795” (Tate Gallery, London).

The city is just off the M4 London to West Wales motorway, and has a regular, direct, train service from London and other places, including Manchester.

Banner photo: City and County of Swansea.

02 What to see and do

Walk through history

The Dylan Thomas Centre is next to the Sail Bridge, in the heart of maritime Swansea. It’s a short step to the National Waterfront Museum, for the story of Wales’s industrial revolution and beyond. The museum is housed in an listed warehouse linked to a modern slate and glass building.

Swansea Museum has four locations – the Museum itself on Oystermouth Road; the Tram shed in Dylan Thomas Square in the Marina; the Museum Stores in Landore and the floating exhibits in the dock by the Tram shed.

The collection includes some large historic objects from Wales, notably a replica of the world’s first steam locomotive, a brick press and one of the few surviving coal wagons. I like the tribute to Swansea Jack, the diving dog who rescued people from the docks in the 1930s.

The Georgian townhouses of Cambrian Place would not be out of place in Bath. Wind Street contains the famous old No Sign Wine Bar. Dylan Thomas liked this ancient, rambling city pub, and set his ghost story “The Followers.” here. This is my piece on Dylan in Swansea.

Much of the centre of Swansea was destroyed in the Blitz in 1941. The Market was rebuilt after the War. The stalls offer the usual market fare, as well as local produce such as cockles, laverbread, Welsh cheeses and Welsh cakes, served fresh from the griddle.

Key run-down city centre buildings have been renovated and brought back into use through a joint public and private regeneration project, the Vibrant and Viable Places scheme. A fund supporting work to bring empty or derelict properties back into use and to enhance building fronts. The Homes Above Shops programme helped private developers to convert vacant commercial space above retail premises into new homes.

Game on

It was a big relief to the city when Swansea Football Club avoided relegation from the Premier Division at the end of the 2016/2017 season, although at the time of writing (Jan 2018) the team is second from the bottom of the division, having won its first game (away to Watford) under its new manager, the Portuguese Carlos Carvalhal. Retaining its place is crucial for the city’s sense of identity. It means the city would continue to receive worldwide TV exposure. Quite apart from the money the club itself receives from TV, fans and sponsorship, the promotion of the wider city in PR terms is incalculable. It’s one of the few areas where Swansea is clearly ahead of its near neighbour Cardiff.

The football club shares the Liberty Stadium, just over a mile from the city centre, with the leading rugby club, he Ospreys.

City of Culture

Concluding a rather depressing 2017 for the city, Swansea heard it had failed in its attempt to be declared UK City of Culture in 2021. This is the second time its bid for city of culture status has failed.

Swansea Lagoon

Another feature making the city distinctive could be the Swansea Lagoon, a project to generate potentially enough energy to power all the city’s homes. This too is in some doubt, at the end of 2017, as awaits approval – or rejection – from the government. If the project goes ahead, the city would attract international attention for a scheme which could be replicated widely.

Electrification of railway line

In 2017 the government announced that the promised electrification of the railway line from London would not now continue beyond Cardiff as far as Swansea. Following that decision, the city is considering a radical transport plan which would include creating a rail bypass, missing out the town of Neath, to cut the travel time between Swansea and Cardiff by 25 minutes, and significantly reducing rail journey times to London. The plan would mark “the foundation of a transformational rail-based Swansea Bay Metro’, which would include creating a tramway along the road from Swansea city centre to Mumbles, finally restoring a semblance of the match lamented Mumbles Railway, closed in the 1960s.

New dual mode (diesel and electric) express trains began running on the route from South Wales to London in late 2017.

Big Hitter

On September 1, 1968, a cricket ball came fizzing into the street out of the famous old St Helen’s rugby and cricket ground, and sporting superlatives were rewritten. Garfield Sobers became the first player in the game’s history to hit six sixes in an over. (A link to an article on my book on the event here.) They have not put up a plaque yet, but it is high time they did. This ground is just one stop on the 4 mile walk (or cycle) to Mumbles along the traffic-free promenade around Swansea’s great curving bay. (There is a Parkrun, starting just opposite the ground, every Saturday morning at 9 AM.)

On September 1, 1968, a cricket ball came fizzing into the street out of the famous old St Helen’s rugby and cricket ground, and sporting superlatives were rewritten. Garfield Sobers became the first player in the game’s history to hit six sixes in an over. (A link to an article on my book on the event here.) They have not put up a plaque yet, but it is high time they did. This ground is just one stop on the 4 mile walk (or cycle) to Mumbles along the traffic-free promenade around Swansea’s great curving bay. (There is a Parkrun, starting just opposite the ground, every Saturday morning at 9 AM.)

Another stop might be the Guildhall, for the vast Brangwyn panels. When you reach Mumbles, pause for an ice cream, light meal or cake in Verdi’s, then tramp over the high grassy hill behind into the beginnings of the Gower Peninsula. Then take the bus back.

Dylan’s den

It was a rare and genuine goose bump moment. I was in Dylan Thomas’s bedroom in 5 Cwmdonkin Drive, where the boy turns down the gas and says some words to the “close and holy darkness” in “A Child’s Christmas in Wales.” Now it is possible to stay in the house and share the magic. Imagine the ghosts of uncles trying out their cigars, and aunties tipsy on the port. The brilliant, wayward poet was born and lived in this house on the steep hill until he left Swansea in his early 20s – around 1934. He wrote half his poems here, including “And Death Shall Have No Dominion.” A local couple restored it to how it was in 1914, when Dylan’s parents bought the house, brand new. It has furniture and fittings of the time and the original colour scheme, but no radio,TV and telephone. It opened in November 2008 for short stays.

You can separately follow the trail of Dylan Thomas in the city. He worked on the local newspaper the Evening Post, went to school at the Grammar School, and frequented many pubs and cafes before you left for London before he left for London.

Coffee stop

Verdi’s, Mumbles

Verdi’s, on the sea front in the Victorian fishing village of Mumbles, boasting “spectacular panoramic views across Swansea Bay” is a family run café, ice cream parlour and restaurant offering “authentic” Italian flavour and quality, and serving home made pizza and pasta dishes, many from traditional family recipes, as well as home made bread, cakes, scones, pastries, semifreddi and desserts.

It also serves 30 different flavours of Italian ice cream using milk and cream from local dairies.

I also like Coffee#1, a chain of outlets owned by Cardiff brewery company Brains. It operates in South Wales and the West Country. Lots of comfy, low down armchairs and the particularly good coffee. Anyone with a sense of history would want to find the Kardomah, but don’t expect to locate the original where Dylan Thomas used to talk endlessly, and I assume soberly, with his friends in the Kardomah Club. That was destroyed in the 1941 Blitz. There is a cafe by the same name at 11, Portland St, and we should be pleased that the name is been saved in this family-run business. “We have maintained the original decor from the restaurant’s opening in 1957.”

In 2014 I was privileged to take a tour of Dylan’s Swansea with his granddaughter Hannah Ellis.

Swansea, though, where his story is anchored. “This sea-town was my world.” I was privileged to walk around it with his granddaughter Hannah Ellis, patron of the Dylan Thomas 100 festival, and Dylan expert Jeff Towns. Jeff knows practically every street the writer ever crossed, on his way to every pub whose bar he propped up in garrulous conversation.

We met close to the now condemned Bush Hotel in High Street, where Dylan took his last drink before his last train to London, and on to New York. Much of the centre was destroyed in the Blitz in 1941, but Jeff finds enough original Swansea to paint his picture.

We walked down Salubrious Passage, where a mischievous schoolboy Dylan would drop coins heated on a Bunsen burner, and watch passers-by pick them up and throw them down with a yelp. We saw the offices of the newspaper where he worked as a reporter, and the BBC studio where that rich stentorian voice would boom at the microphone in many a live broadcast. And the former Swansea School of Art where the platinum-tongued lothario chatted up my mother, a student there.

One of the least changed locations is Waterstones bookshop in Oxford Street. This used to be the Carlton Cinema. Dylan knew it well. It still has the original ornate staircase in what was the foyer.

The Kardomah Cafe, where he spent so many teenage days with his friends, was destroyed in the Blitz. We called in at the “new” Kardomah in Portland St, now historic in itself, for a pot of tea and a custard slice.

Art with soul

Frank Brangwyn was an artist of two nations, honoured in his native Bruges, but let down by the British establishment. London’s loss was Swansea’s gain. Brangwyn’s father was from Buckinghamshire, his mother from Wales. They moved to Bruges where Frank was born. The family returned to England, where his talent blossomed. He received two separate commissions from the House of Lords in 1925 as a memorial to the First World War, but both, WW1 battle scenes – “too grim”, and the British Empire Panels – “too colourful”, were rejected by the peers. Today they hang, respectively, in Cardiff’s National Museum of Wales and Swansea’s Brangwyn Hall in Swansea’s new Guildhall, where they were placed in 1934.

The Arentshuis Gallery in Bruges holds 400 works he donated to the city, dark, sinewy paintings and drawings extolling honest toil, shipyard workers dwarfed by the monster vessels they built

Finer than Naples

The poet Walter Savage Landor, who lived for a time in Swansea, is often quoted as saying the city was more beautiful than Naples. This is what he actually said: “The Gulf of Salerno, I hear, is much finer than Naples ; but give me Swansea for scenery and climate. (Walter Savage Landor: A Biography – John Forster,1869.) But the artist Joseph Mallord William Turner was there first.

His “View across Swansea Bay 1795” in his “Smaller South Wales sketchbook” is in the Tate Gallery in London, although it’s not on show. This was one of two sketchbooks that Turner took with him on his tour to South Wales in the summer of 1795.

The Tate catalogues it thus: “Pencil on white wove paper, 130 x 205 mm; Inscribed by John Ruskin in red ink ‘14’ bottom right.”

The Tate adds on its website:

“Swansea Bay enjoyed a reputation for great beauty in the period of the Picturesque tour of Wales; the poet Walter Savage Landor (1775–1864), who owned property there and so might be considered prejudiced, opined that it was the equivalent for natural beauty of the Bay of Naples.”

Gallery reopens

The Glynn Vivian Art Gallery re-opened in 2016 after a five-year refurbishment.

It was founded in 1911, and is named after the local industrialist Richard Glynn Vivian. The gallery and museum has developed a significant collection, covering a broad spectrum of the visuals arts from old masters to contemporary artists, with an international collection of porcelain and Swansea china.

The re-opened gallery also shows artefacts its founder Vivian collected on his world travels in the 19th Century.

It also hosts national and international touring exhibitions of major contemporary artists and art historical shows. Some major pieces have been on temporary show thanks to the Glynn Vivian’s status as partner in Plus Tate – a major collaborative arts initiative with London’s Tate Gallery.

Attic Gallery

The Attic Gallery, Wales’ longest established private gallery, dates from 1962. It highlights the work of contemporary artists working in Wales.

It is now in the Maritime Quarter, showing the work of some of the principality’s most important artists. There is a programme of individual exhibitions, with a changing display of new paintings, graphics and sculpture.

The Norwegian Church

The Norwegian Church. (Photo: BBC)

Swansea’s longstanding connection with Norway began when timber pit props were imported from the country for use in the coal mines of South Wales. Welsh coal was sent to Norway in the return trade.

The Norwegian Church was opened in Swansea in 1910 to serve the spiritual and social needs of Scandinavian sailors. It had originally been erected in Newport Docks in the 1890s, and was moved to Swansea.

The church used to stand at the Main Entrance to Swansea Docks. The original decision to close it came in 1966, as the number of Scandinavian seamen visiting the port declined. But a Norwegian living in Swansea ran the mission, with the help of Swansea’s Norwegian community, for a further 32 years, until its eventual closure in 1998. In 2004 the building was dismantled, restored and relocated to its present position in the maritime quarter.

Heart of Wales railway

Dr Beeching’s red pen must have hovered long over this glorious 120 miles long epic from Swansea to Shrewsbury, through some of the most majestic landscape in Britain. He summarily axed so many other rural routes in the 1960s. Why not this one?

By rights this far-away stop, indeed the whole of the Heart of Wales Line, should have been consigned to the history books, along with milk churns, Bernard Cribbins look-alike porters from the Railway Children, and racing pigeons in baskets waiting to be released.

Sentiment, still less tourist potential, did not come into it.

The reason was business. The line survived only because it also carried freight.

It takes about four hours from Swansea to Shrewsbury. (Originally the line ran from Victoria Station in Swansea, which was shut in the 1960s. For the start of the journey trains follow the alternative, more northerly line to Llanelli.)

Further reading

Further reading: Thomas Cook Pocket Guide Swansea, by Victoria Trott. http://www.victoriatrott.co.uk/books/4580547784

03 Where to stay

Red brick boutique

Morgans is a boutique hotel born out of Swansea’s great nautical past. This handsome Victorian building, red brick banded with Portland stone, was mission control for Swansea’s trade when it sent ships round Cape Horn as far as San Francisco. In 2002 a local businessman gave it this new purpose – I’m sure an earlier Swansea would have let the building go, just as its misguided leaders let the Mumbles Railway close. Many of the original Art Nouveau details survive, light fittings, pillars, wooden floors, and stained-glass windows in the cupola above the original staircase depicting points of the compass. We stayed in the Benjamin Boyd; all the ample, high-windowed bedrooms take the name of ships that sailed from here.

04 Nearby

Kenfig National Nature Reserve, one of the finest wildlife habitats in Wales, is one of the last remnants of a huge dune system that once lined the coastline of S Wales from the Ogmore River to the Gower peninsular. It is still part of the largest active sand dune system in Europe, and contains the natural lake Kenfig Pool.

The reserve contains many rare and endangered species of plants and animals, including the Fen Orchid. It is a refuge for wildfowl year round and is one of the few places in the UK where the bittern can be seen during the winter.

Gower.

Gower, jutting into the Bristol Channel like a fly half’s boot aiming a drop goal at Devon, begins in Swansea’s eastern suburbs. The entire peninsula was named the UK’s first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in 1956. The south-facing coast is garlanded with great beaches — Langland, Caswell, Three Cliffs, Oxwich and Port Eynon. Rhosilli is the finest of all, a three mile sweep of sand under a towering bracken-smothered hill. Inland is a spine of high moorland studded with brimming ponds, as creepy and romantic as Dartmoor. And as wild as Africa. The offspring of old pit ponies released here still run free. In the deep leafy heartland you plunge down a mystery maze of lanes, which usually lead to a castle. Such as Oxwich, stout and intact, or Woebley, worn and cryptic.

Read my feature on Gower here

Where to eat on Gower.

The three times we ate at the excellent restaurant at Fairyhill, one-time Welsh Restaurant of the Year, all happened to be wild nights. On our last visit to the rain lashed us across the car park of this small country house hotel in one of Gower’s remoter folds, but still only 20 minutes from Swansea. Which only made the cosy repose inside, as we were served Penclawdd cockles in batter with Welsh G&T (Penderyn gin), all the more welcome. (They offer 100 different gins, served so many different ways.) You feel safe from the world here. Most of Fairyhill’s ingredients come from within 12 miles, from the hotel’s own gardens, or the peninsula’s rich larder. www.fairyhill.net.